Growing Fruit in Containers

As my wife (who is driven round the bend by this trait) will testify, I am a stickler for detail so I couldn't bring myself to reply in a few short sentences and thought I might as well use the question as the basis for a newsletter and blog. I am, by the way, always more than happy to answer any queries (where I can) so please feel free to contact me any time.

The only question that makes my heart sink (and one that gets asked a lot) is some variation of 'How do I start a vegetable garden?'. I mean, how do you answer that in a couple of sentences? How long is a......

The question in question

OK, so here's the bones of our customer's fruit tree question:

I moved into this place a year ago and I noticed that my garden is essentially a bog when I started working outside. So I don't want to kill the trees by leaving them in a two-inch water-logged garden.

The fruit I would like to plant are: 3 tayberries, 3 apple trees, 1 pear and 1 victoria plum, all trees will have to be in pots from now on unfortunately. This year we bought 2 cherry trees and planted them in the soil but I'm not sure those will survive the water logged ground. So now I'm looking at a solution that allows me to have fruit trees. I just got a fantastic sale price on really big ceramic containers for my future fruit trees, I would estimate they are 45cm diameter and 55cm tall.

The answer(s)

The difficulty in answering comes when one starts to type a reply, as the following points come to mind (if one is to do one's best):

- Almost any plant - especially large specimens like fruit trees - are better in the ground than in a pot.

- If growing in a container, you need to use the correct rootstock.

- The pot needs to be large enough and filled in a way that doesn't cause waterlogging.

- Container-grown trees need extra feeding and pruning.

- Some soft fruit (e.g. the tayberries in the question) may not be ideally suited to container or small space growing.

So, here we go:

Most plants do better in the ground than in a pot

A waterlogged garden is a major problem, because plant roots need oxygen and can't survive without air spaces in the soil. On the other hand, containers create an enclosed space and mean that plants need a lot more support in terms of watering and feeding: this is especially true when dealing with large plants like fruit trees.

The following may have been explored already, but I would be inclined to look at ways to overcome the drainage issue before going straight to container growing. Open ground is a better home in the long term.

A wet garden can be resolved by installing land drains. This process (pictured above) requires digging trenches approximately 40cm wide by 90cm deep, and installing perforated land drain pipes on a bed of gravel. The trench is back filled with gravel and can be finished off with a shallow layer of topsoil to conceal the drain. Obviously, the water has to go somewhere - so the land drain piping needs to be funneled into a domestic drain system or into a gravel filled sump (a large hole filled with gravel).

Raised beds are also an effective way of dealing with a wet site by raising the root zone above the waterlogged ground. This will be even more effective for drainage if trenches are dug between the beds and filled with gravel or other free draining material. The topsoil dug from the drainage channels can be used to fill beds: this is the method I used in my own wet garden, and one that has proved to be very effective. I would certainly consider a raised bed system over containers where possible but if the site can't be improved, a large pot is still a viable option.

Rootstocks

Back when we were all running around in bearskins and grunting at each other, apples were all relatively large trees bearing small, bitter fruit. I was going to say we have both come along a lot since then but given global events, I think the apples might have the upper hand.

Apple fruit has been progressively bred over thousands of years to give the range of sweet varieties we have today. The ability to control the size and vigour of a tree using rootstocks was only developed in the early 20th century, which also allows us to grow trees of the same variety at different heights.

The point here is that it is the root which governs the size of the tree, so a slip of live wood from the desired apple variety is grafted onto a rootstock of the desired size. Once the graft has set, the join will be covered by new bark - but if you look near the base of a young fruit tree, you will see a swelling where the tree and the root meet.

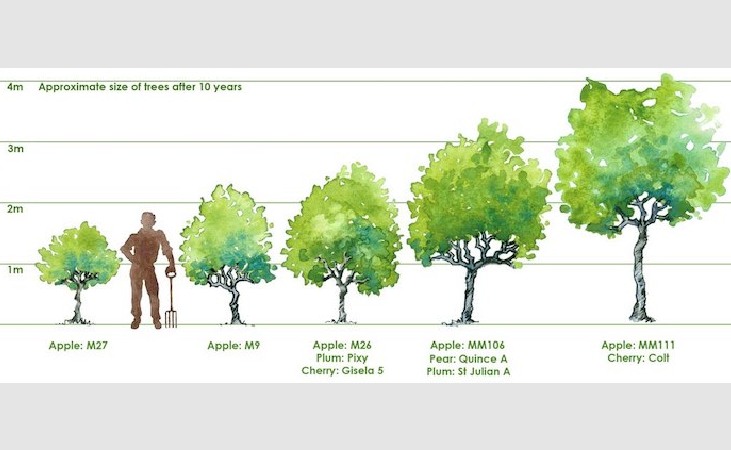

Rootstocks are relevant to our customer's question as - if growing in a container - she needs a very dwarfing (M27) or a dwarfing (M9) rootstock to produce a compact tree that is comfortable growing in the confines of a pot. In my opinion the M9 is the better option for yield, as M27 rootstocks produce a very small novelty type tree.

View Pirouette Apple Trees M9 Semi Dwarf

It is possible to use larger rootstocks like M26 or even MM106, but they are more work to control and should ideally be root pruned every second year and replanted in fresh compost. Trees like this with larger, more vigorous rootstocks will actually crop better than the dwarfing varieties if expertly pruned, fed and watered but, er, very few people are experts.

Size of pot and potting mix

Naturally, we need a pot large enough for the tree. The size will depend on the rootstock used (and therefore the expected size of the tree) but for an M27 or M9 tree, 45-50 cm wide is about right - although a larger pot will mean less watering.

To fill the pot, I would recommend using a soil based compost. It will hold water and nutrients better than a soilless mix, and it's also a bit heavier which helps prevent the pot from blowing over. A good option is John Innes No.3 (produced by a number of different brands) which contains approx 55% loam soil, 25% peat or peat free compost and 20% horticultural grit.

If you have a number of large pots to fill, I would recommend our own Quickcrop bulk bags of container growing mix: with a breakdown of 60% Premium Screened Topsoil, 25% peat reduced compost, 15% horticultural grit and 4kg seaweed & poultry manure pellets.

View Container Growing Soil Mix - 750l Bulk Bag

Don't put gravel in the bottom of your pots - the science bit.

You might want to tune out for the reason why (it goes on a bit), but basically you shouldn't put gravel in the bottom of a pot to improve drainage - as it will actually have the opposite effect. This is a controversial subject with gardeners but, as is often the case, we can't argue with the science as follows:

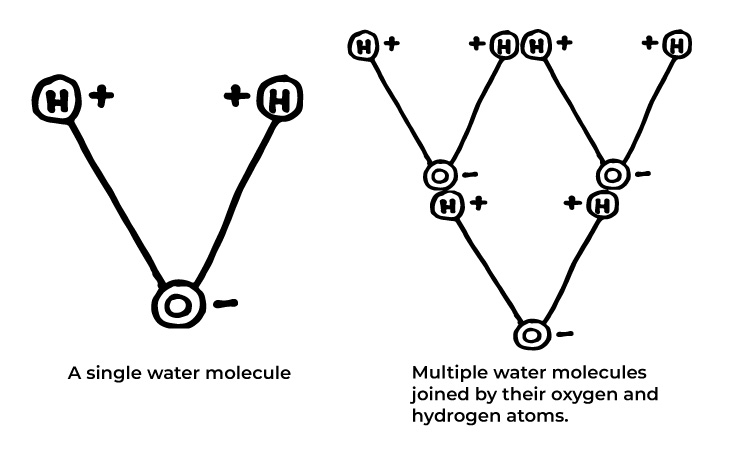

Water, as you know, is made up of one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms. The relevant part is that oxygen is negatively charged while hydrogen is positive; negative and positive charges attract each other which means water sticks to water as the hydrogen atoms stick to the oxygen on neighbouring water molecules.

Water also sticks to other negatively charged particles so, because all soil or compost molecules carry a negative charge, water also sticks to soil. This gets interesting when we learn that the more dense (smaller particle size) a soil is, the higher the negative charge it carries. Therefore a clay soil with a fine particle size has a higher negative charge (more sticky) than a sandy soil (less sticky).

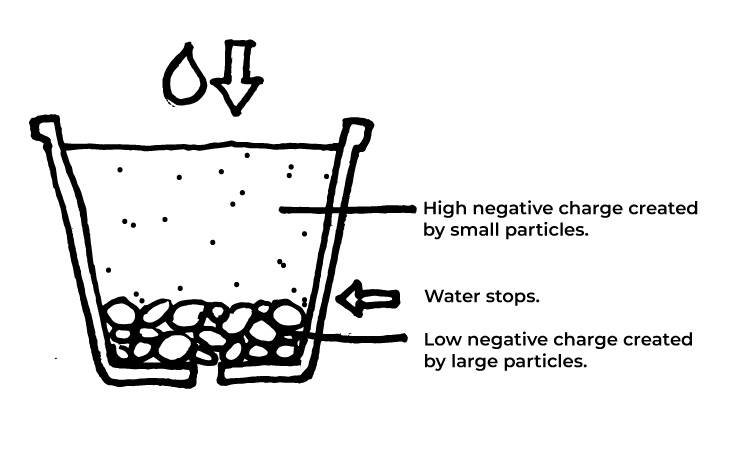

The issue with the gravel at the bottom of the pot is that (due to its very large particle size) it has a much lower negative charge than the potting mix above. This is a problem because, when water percolates through soil and encounters a band of material with a lower negative charge, it stops.

The result is that the potting mix gets completely saturated, meaning all the air spaces between the particles are full of water. Roots need oxygen to breathe so if a pot is permanently saturated, the roots will die off and rot.

You may be thinking, hang on - I have pots with gravel in the base but water does come out the bottom? This is because if you add more water to a saturated pot, gravity will force water out the bottom while the potting mix remains saturated. The only way for the pot to dry out is through evaporation from the soil surface or from plant roots sucking it up.

So, when filling a pot, it is best to use a mix with the same consistency throughout.

Planting a fruit tree

To plant a fruit tree, half fill the pot with the compost mix to the point where the bottom of the root ball will be. You can add in a small handful of blood, fish and bone meal at this stage because it is high in phosphorous, which will encourage strong root growth. It can also be a good idea to put a stake in the pot at this stage to provide extra stability, as wind rock can break developing roots and slow the establishment of the tree.

Once the root ball is in, you can back fill the pot, gently firming in around the roots as you go (especially if you are planting bare root stock). If you have a pot grown tree, the finished soil level should be the same as it was in the nursery pot. If you have a bare root tree, you will see a change in colour at the base of the stem which marks the original soil level.

Soft fruit suited to container growing

Provided you have a large enough container and the right potting mix, you can grow almost any soft fruit in a pot but - due to their habit - I think some options are better suited than others.

Let's look at the tayberries (above) mentioned in the question. The plant itself will be very happy in a pot but, due to the fact that it is a hybrid cross with a blackberry (bramble) and a raspberry, it is quite an unruly plant that needs a bit of training.

The image above is a tayberry in winter showing the growth produced in the summer just passed which has been trained for next summer's fruit. The fruit is always produced on the previous year's growth, so in any given year you will have 1 yr old fruiting canes and new canes being produced for the following season's harvest.

Once fruiting has finished, the old canes are cut out down to the base of the plant, while the current year's growth is trained onto wires as shown above. Given that tayberry canes are prickly and grow into each other, you need a good bit of space to train a plant easily and keep it productive. Any hybrid berry (tayberry, boysenberry, loganberry) grows in the same way so the above applies to them all.

Raspberries produce vertical canes so don't need to be trained on wires, but you do need a decent number of canes to produce a worthwhile crop. For that reason, I don't think they make great container grown plants - but they work very well in raised beds as above (the line of sticks in the middle are a mix of summer and autumn fruiting raspberries).

I have the same wet site problem as our customer but, as you see above, I have raised the soil level using timber boards held in place with pegs. I completed this job 5 or 6 years ago and so far all is working well: with one of the worst parts of my site now being a productive space. I think the same treatment may be the better option for tayberries, rather than wrestling with them in a pot.

What soft fruit does do well in pots?

As regards what soft fruit does do well in pots, I would look at plants with a bush habit like blueberries (you will need an acid or 'ericaceous' potting mix), currants (black, red or white) and gooseberries, as they don't require training and can be easily kept under control with annual pruning.

Strawberries, of course, are absolutely ideal as they are compact plants that are very easy to grow. Good quality fruit can also be easier to harvest from containers, as much of it hangs around the edges so isn't in contact with damp soil. If you have a greenhouse or polytunnel (and a strong back), planting in pots gives a further benefit as you can achieve bountiful early season harvests under cover - although they will need to go back outside in winter to flower properly the following year.

Watering and feeding container grown fruit

A container grown plant has a much smaller feed and moisture bank to pull from than one planted in the garden soil, as all its requirements must be met by whatever material is inside the pot. The feeding roots of pot plants can't spread as much as they would like, nor can a fruit tree put down a moisture seeking tap root into deep soil. The success or failure of potted plant is therefore down to us.

Water (or lack of) is a limiting factor for container grown fruit trees, as a full canopy of leaves can drain a pot very quickly in hot weather. Inconsistent watering during the flowering/fruiting cycle can also lead to fruit drop so - given that you only have one shot at producing fruit per season - I feel an automatic pot watering system is a sensible investment. These systems are relatively inexpensive and consist of individual drippers (above) on a micro hose system that feeds each pot separately.

View Article: The Quickcrop Garden Irrigation System

Feeding is much easier with a dressing of seaweed and poultry manure pellets every 6 months or so, providing slow release nitrogen for leaf growth. I would also recommend using a liquid tomato feed to provide potassium during the fruiting cycle: use from when fruit is set right through to harvest. I can't make the point strongly enough that if you want to get a satisfying crop from container grown fruit, especially tree fruit, you need to keep your plants well fed.